A few years ago, I attended a book launch in Rome where a chef, as part of a panel, spoke about waking up in the morning as a young boy and knowing what day it was by the smell of his mother’s cooking which would emanate into his room and find him underneath his covers. This smell carried with it, the traditional Italian post war menu planning that arose around religious rhythms in Italy, but more specifically in Lazio where the saying ‘Thursday gnocchi, Friday fish and Saturday tripe’ developed within Roman culture. The idea being that a family would consume a more substantial dish such as gnocchi on Thursday to get through a lean ‘magro’ day of fasting on Friday where things like fish and beans, like ceci for example, might be consumed. Tripe, one of the offal offcuts, would be eaten on Sunday by the populations’ less affluent as part of their ‘cucina povera’. It’s still a rhythm followed by many homes and restaurants who continue to cook up the same dishes on various days of the week with seasonal variations on theme.

The experience of waking up to ‘the smell’, is a cross cultural experience that many of us know well, especially around the holidays, where certain members of the family rise before dawn to procure abundant, slow cooked afternoon and evening meals. Up until recently, before we reacquired our Italian home, it was also an experience that I could appreciate when we stayed with my mother-in-law who would also rise before dawn to start a meal before returning to bed. More often than not, the warm smell that filled every room in the house was that of beans.

And yes, I really do love a warm, freshly cooked bean, lightly salted and splashed with the new, first press olive oil.. do you know? If not, you should know. It can be hard to restrain oneself in front of the hot pan. The height of the bean experience, in my opinion, is when they are traditionally cooked close to the burning hot embers of an open fire in a handled pentola di terracotta or pignolo. Slowly. For hours. It’s definitely a taste experience to add to any culinary bucket list.

Known as the ‘meat of the poor’, again as part of the now much sought after cucina povera, beans and legumes, mostly planted in the spring and harvested in the second half of August, have always offered a fundamental source of high quality plant based protein in the diet especially during the winter months often consumed in the warm and nourishing minestre that are still popular today. They are high in iron, B vitamins and fibre, and really versatile.

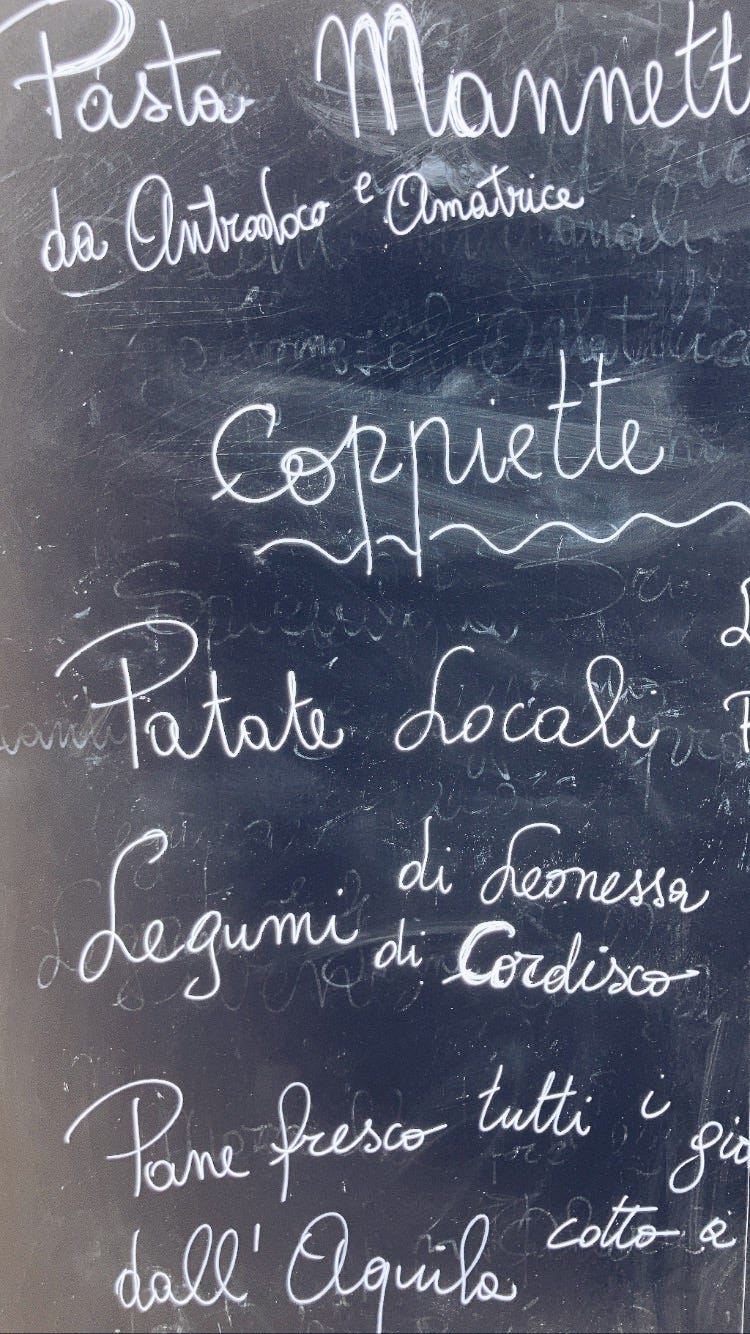

Beans and legumes form part of the culinary identity of Central Italy and continue to animate many dishes cooked within the daily life of these borders. Lazio does a biodiverse bean really well, with more than 22 unique varieties of beans and legumes celebrated as part of this region’s agricultural excellence. Many of these beans are grown in Sabina, in the province of Rieti, and while Umbria’s altopiano of Castelluccio has gained popularity for its beans and legumes, many are unaware of the quality of similar products that spring forth from places like Lazio’s fertile high plain or plateau of Rascino, 1200 meters above sea level about 2 hours northeast of Rome. The bean and legume products coming from these regions interwoven throughout the Appenines have a unique taste, colour and consistency that is hard to beat.

In the future, fresh and dried beans should be easier to come by in our local food systems as they are being recognised and reintroduced for their important role in the development of sustainable food models and agricultural plans especially where peas and beans were historically consumed as part of a traditional diet, before the introduction of industrial crops and the processed meat machine models that we see today. It’s a crop that creates a break for cereal rotations, provides a resource for pollinators, promotes soil biodiversity and the overall greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with legumes is low.

‘The Farm to Fork strategy is at the heart of the European Green Deal, aiming to make food systems fair, healthy and environmentally friendly. The Farm to Fork strategy recognises the role that native protein crops can make in achieving these targets.’

While I do love cooking a fresh beans when in season to prepare all’agro, I tend to cook dried beans, slipping them into all of the places where I would usually use meat. We do eat meat in our family trying to keep it as local and organic as possible, but we are always consuming less and less. We include beans and legumes in the ingredients that we tend to haul back from Rieti, and when these run out, I flip over the bags in the supermarket and try to choose whatever bean is grown closest to where we are at the time. Canned beans feature in our kitchen as well, but really, the taste and texture of a freshly cooked bean does not compare. They are extremely economic and easy to cook and our kids love them.

This minestra di ceci or chickpea soup also features in our kitchen in many forms and calls for 6 ingredients more or less. The underpinnings can produce a vegan dish, but anchovies, lardo, pancetta or guanciale are often used to create the soffritto that serves as a base for this recipe. I have to say I think the use of guanciale provides the most satisfying result, and the discovery was accidental. So many dishes, that come from the cucina casereccia, are not much to look at but are delightfully surprising when it comes to taste. By following these few simple steps, you can’t go wrong:

Ingredients:

Serves 4-6

500g of dried ceci

1-2 cloves of garlic finely chopped

1 small onion finely chopped

2 small sprigs of fresh rosemary

2-3 quality plum tomatoes fresh or canned

50-100 grams of fresh or dried pasta*

25g guanciale finely chopped, optional

1 small peperoncino, optional

Sea salt, freshly ground black pepper

Method:

Soak your beans in tepid water overnight. Drain and add them to a medium pot and cover with water. Add a small sprig of rosemary. Bring the ceci to a slow boil and immediately turn down to simmer half covered according to the cooking time indicated on the package. Add a pinch of baking soda halfway through and salt toward the end. Top up with more water while cooking if necessary.

Create a battuto of finely chopped garlic, onion and rosemary adding the guanciale to the vegetables if you decide to use it. Cover another medium heavy bottomed pot with a thin film of olive oil. Add the battuto to the oil as well as the peperoncino if desired and cook stirring with a wooden spoon over low heat until the vegetables are soft. Add the tomatoes to vegetables crushing with the back of the wooden spoon. Simmer on low for a few minutes stirring, taste and season. Ladle half of the ceci into the pot (saving the rest for another use) together with their cooking water and then add some extra water if necessary. *Here you can add fresh or dried pasta, regular or gluten free in the form of quadrucci, sagnette, cannolicchi, ditalini broken linguine or spaghetti. Simmer again on low about 30 minutes. Taste before serving with a drizzle of oil and some freshly ground black pepper.

Notes:

Some will add salt to the soaking time or at the beginning of the cooking time, but I do not recommend this, as it could cause the beans to split.

You can add or subtract the amount of pasta according to your own taste.

You can also add some vegetable stock here if needed, but it should not be necessary.