The Stroncatura Pasta of Southern Calabria

Another Italy. When the Tip of the Boot Gets Inside of You.

‘Quando un forestiero viene al Sud piange due volte: quando arriva e quando parte.’

‘When a stranger comes to the South, he cries twice: when he arrives and when he departs.’

- Benvenuti al Sud (Welcome to the South)

I could not see through the darkness on the brief tour that Riccardo gave me as we drove through the abandoned streets on our first night in Palmi. He had accepted a position to work in the ‘administrative offices’ for the company that was responsible for constructing the macro lot that stretched from Gioia Tauro to Reggio Calabria as part of the A3 highway from Salerno, an artery upgrade to facilitate the flow of fresh blood to and from the South. I drove down this broken orange cone marked flashing light tract as his fiancé or fidanzata who was yet to learn that it is possible to be loyal to a fault. I went, despite all the warning signs.

The following morning after Riccardo departed to work in the dusty, solider guarded camp, I stepped out of the hotel into the white-hot light, onto the busy rotary and scanned the worn and half-finished iron exposed roofless concrete buildings surrounding me. Afraid, I started down the dirty roads to glance into the windows of the mom-and-pop shops until I stopped for a very long time to stare at the breathtaking view of Aeolian islands as a distant backdrop to the glistening Mediterranean Sea. In the burning midday heat, I found myself alone on the stage of the grand piazza, once host to the prosperous and tragic scenes of history, with its layers of ornate architecture framing an abandoned and crumbling Hollywood set. The only thing missing, I thought to myself, were the tumbleweeds.

I called Riccardo with tears in my eyes and whispered into the phone ‘I cannot live here, it looks like Beirut [postwar]’, but we did live there because, in the current economy, we didn’t have a choice. We prayed for our annual contract renewal over the next 5 years as we laid a somewhat lonely foundation for our young family as we moved along the coast living, loving, losing, learning, and most importantly cooking and eating to become one with and understand our community and home.

When one arrives in Calabria it is easy to see her, at first glance, as one of the black-veiled widowed fishwives of Palmi’s Tonnara and to hear the lament of the people through their cries. You do not have to squint to see the poverty, unemployment and oppression, inequalities, corruption, and the cancer of the mafia which we lived among (hence the loneliness) but I am not qualified to talk about.

I was once operated on in a soiled overcrowded maternity ward with no hot water and bathrooms that you might see in prison (we were like a large herd of cows), we had a huge rock thrown through our living room window as we watched TV (scary when your husband specializes in anti-mafia), one of my fellow teachers of 50+ years could not go out for pizza without an escort and our daughter played amongst the rusty nails of broken playgrounds, not to mention the ever-worsening mountains of toxic trash piled high in the streets (spinning through the air come winter) that should be a major public health concern.

With its pristine waters, position, and incredibly rich cultural heritage, Calabria is one of the jewels in Italy’s broken crown, the part she wears in the back. The realities that I have recounted through the eyes of my personal experiences are a glimpse of everyday life for your average Giuseppe here and in the more disadvantaged regions of Central and Southern Italy. These realities are quite far from the alluring and highly curated images of Italy’s dolce vita that we see on social media. And for the last 13 years, I have been wondering why no one talks about these disparities.

Calabria, once part of Magna Graecia (Great Greece) still evident in both the cuisine and local Greco-Calabro dialect, kicks her regal and royal boot out into the historical crossroads of civilization. She is the home of language, mythology, and great minds. She is wild, raw, beautiful, real, and inspiring. Like any great romance, I fell deeply in love with Calabria despite her faults, and I am so thankful for her opportunities and gifts - the ones that shaped us into who we are today.

In the weeks that followed the tears, La Signora or ‘Donna’ Mimma and Rosaria, the mother and sister of Riccardo’s close pal, took us into their fold and made us family. We became witness to Calabria’s unparalleled warmth and hospitality, to its history, facades, landscape, and climate. Most importantly as farmers dropped crates of vegetables and the freshest ricotta to the door, as we watched fishing boats glide across the sea, and as we ventured into the plain for fresh citrus, as we perused her markets, we began to understand Calabria through her prestigious primary ingredients and the bounty of her food. ‘Soo-gnu amer-i-cana ma ten-go pear-en-ti Cala-bre-se’ – ‘I’m American but my family is Calabrian’, was the phrase that they taught me so that I could pay the same prices as locals at the markets.

A few weeks ago, we finally drove down onto the Violet Coast to show our Made in Calabria children the fruit of their origins and the land which nourished them into life. It was an emotional return. On our way down memory lane, we passed through Gioia Tauro and over to the Tonnara of Palmi to visit our beloved Nonna Mimma. As we rounded the bend, we stopped at our favourite produce stand to secure the contraband pasta that is ‘la stroncatura’.

Struncatura (in dialect) is a traditional pasta from the plain of Gioia Tauro that over time has also become part of the gastronomic and cultural heritage of Gioia Tauro, Palmi and other towns dotted through the Aspromonte region of the Calabrian Appennines.

Representing Calabria at the World Expo in 2015, and celebrated at local sagre (food festivals) in August, the origins of this pasta date back to the 18th century, when Gioia Tauro and its port established themselves as a major trading centre which was heavily frequented by the many Amalfi merchants who inspired this practice in the local cucina povera.

It was during this space in time when poor local factory workers and their families began to collect residues of wheat milling and bran swept up from the ground to knead and cut by hand. It is unclear whether the name comes from its shape or this gesture, but stroncatura was deemed unhygienic in the 19th century and banned for human consumption. Today artisanal pasta factories produce a linguine shape through bronze drawing methods using water, whole durum wheat semolina and rye. It has a very unique colour that I love with a porous rough texture that makes it ideal for absorbing sauce. Buying struncatura, which is still wrapped in brown paper and kept under the counter in local produce stands, feels like a very naughty thing.

The strong spicy sauces created to mask the less-than-appealing flavours and textures of those times are still used today. From mare to monti residents are melting umami-packed anchovies in olive oil-glazed pans and tossing in fat-smashed cloves of garlic which the neighbours can smell from afar. They are adding the bright red tomatoes bursting from their gardens, tiny fresh hot peppers hanging in a low bush, salted capers quickly rinsed in their fingers and local briny black olives. The garnish, freshly chopped parsley together lightly toasted bread crumbs, known as the moreish cheese of the poor, make this dish dairy-free.

La stroncatura, a pasta that I probably made several times a week in slightly different ways with ingredients that I always have to hand, has been my favourite go-to cupboard pasta since our time in Calabria. The easy-to-make ‘condimento’, as mentioned above is quite close to the ‘puttanesca’ of Naples or ‘pasta atterrata’ which is eaten on the Amalfi coast on Christmas Eve – but somehow it hits different.

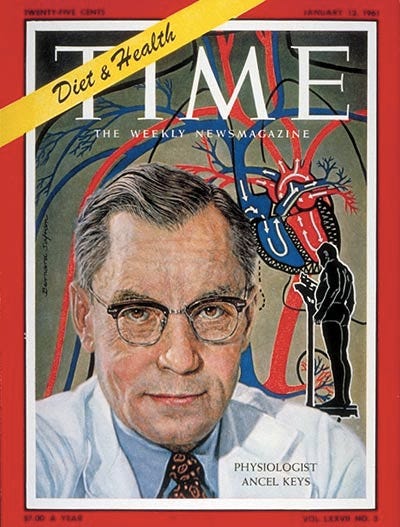

The history of these two regions is also tangled up in the foundation of The Mediterranean Diet as Dr Ancel Keys, an American physiologist, lived in and conducted his studies both in Cilento just south of the Amalfi coast, and in Nicotera just north of Gioia Tauro. Wholegrain dishes like la stroncatura as part of this longevity and quality-of-life supporting diet, help to balance blood sugar levels and the anchovies and olive sources used are an excellent medicinal source of antioxidants, vitamin E, calcium and Omega 3.

Through the years we would watch the sun set behind Stromboli smoking, reflecting every kind of pink onto the calm milky sea and a beautiful thing would happen as the night closed in. Little boats would appear. One, then three, then five spaced perfectly apart and one by one they would turn on lamps in the stillness, like fireflies. This vision would always stop me in my tracks and still today, it’s one of the most beautiful things that I have ever seen.

At the time I didn’t realize that I was witnessing an ancient and sustainable fishing method called la lamparata used to catch various species of ‘pesce azzurro’ or blue fish such as mackerel, sardines and of course the anchovies that are at the centre of this recipe. When the anchovies start to melt in the pan, I am instantly transported back to these moments in time.

Whole-grain pasta and bread, still a source of trauma and shame for past generations of Italians for the memory of poverty and hunger that they hold, have now become a highly sought source of cultural heritage, culinary history and pride. As are the sustainable and traditional food and lifestyle ways and critical knowledge preserved within these landscapes that still feel as if they have been untouched by time.

When we choose responsibly sourced and grown artisan ingredients, cook and share an authentic traditional recipe, and make mindful decisions to understand the cultural heritage and stories that rise from the steam of our plates, we have the opportunity to engage in revolutionary mutually empowering and regenerative acts that raise the vibration of humanity. To engage in acts, that reveal the light.

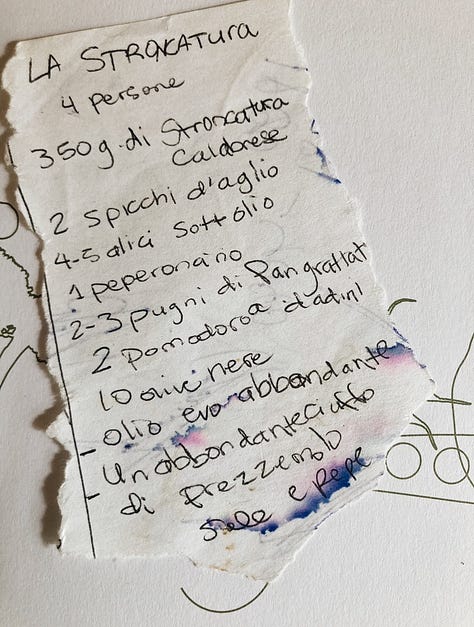

Look for stroncatura in your local Italian grocery or online. I’ve seen this dish made with various combinations of tomatoes, olives and capers. Every chef or home cook will argue that theirs is the right way. What remains constant is the use of garlic, spicy red pepper and anchovies. Below is my preferred method, slightly adjusted from a recipe that I was given by a woman on the beach in Palmi. Feel free to make it your own.

La Stroncatura Calabrese

Spicy Whole Grain Pasta with Anchovies

GF + DF

Serves 4

Ingredients:

400g stroncatura or whole grain linguine, regular/gf

2 cloves of garlic

4-6 anchovies packed in oil

1 small dried red pepper

2-3 handfuls of breadcrumbs, regular/gf

2 small tomatoes peeled and diced or 8 cherry tomatoes halved

1 small handful of olives* roughly chopped

A small bunch of parsley finely chopped

1 tbsp of capers – optional

Drop of white wine - optional

Extra virgin olive oil

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Method:

1. Lightly toast your breadcrumbs in a wide dry frying pan over low/medium heat stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon. When they start to colour add half of the parsley together with a drizzle of olive oil. Stir and remove from heat.

2. Fill a medium/large pot with water, bring it to a rolling boil and add salt. When it comes back to a boil, add your pasta, stir, and cook until al dente.

3. While your pasta is cooking lightly coat the bottom of a wide frying pan with olive oil. Warm over low heat and add the crumbled pepperoncino together with the crushed cloves of garlic. Remove when they are blond, then add the anchovies lightly crushing them with the back of a wooden spoon until they melt into the oil.

4. Add your olives, tomatoes, capers and wine if using, and the other half of your parsley. Cook over low/medium heat stirring until the tomatoes start to break down. Taste and season if necessary.

5. Drain the pasta al dente reserving a small cup of cooking water and add it directly to the pan gently tossing to combine. Add a few splashes of cooking water to loosen if necessary.

6. Generously sprinkle each bowl with breadcrumbs and serve immediately.

Notes:

A black Calabrian olive is ideal here. If not, any quality Italian olive, preferably from the South will do. Feel free to finely chop or slice your garlic for a stronger flavour.

Beautiful!